Wings

A Rosary for Saint David Wojnarowicz,1954 - 1992

There is this place I come from I guess you could call it a topographical plane I’ve only studied it from above and I don’t remember how to get into its recesses it is a maze, made up of dark dark red squared spirals and I can get back there by pressing hard on my eyelids in my memories of this place I’m scanning atop it maybe flying but bodiless more or less and we are all there but no one is there either and it’s a shared plane but it’s temporary (insofar as time applies there, which it does not) and I am not able to bring someone with me, but if I could I might fly over it with Saint David’s hand in mine.

1. Creed

I believe in Saint David, who reaches his warm hand to me in the night.

I believe in the geometric plane from whence I came. I remember, vaguely, this entrance. If I press on my eyelids hard enough, I can return there for a moment, this fleshy, mathematical plane to which I will one day return for good.

I take Saint David’s hand. I consider flight. I consider that he too might know this geometric plane.

Do blind men have visual dreams?[1]

So asks Saint David.I wonder, then, if the plane which I am ‘seeing’ (an impoverished word) is pre-visual, or post-visual, if it is visual at all. Am I seeing when I press on my eyelids until I cannot see? Did the children of Fatima see the virgin? Did Moses hear the burning bush? (Saint David, wings of fire, there the angel of the Lord appeared to him in fire from within a bush).[2]

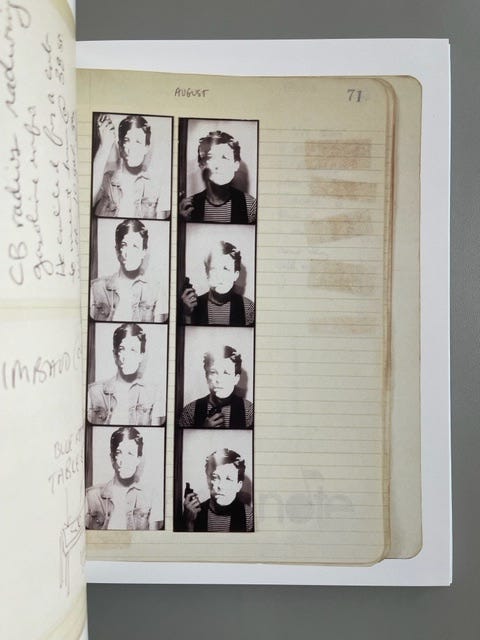

Saint David, after his ascension, left:

Notebooks kept over two decades

A rich epistolary archive

Super 8 films and silver negatives

Paper masks

Lovers

In looking out the windows I can place myself somewhere outside in the sky, lie down in that texture and dream of years and years of sleep.[3]

Yes, Saint David knew flight. Knew my geometric plane.

2. On Wojnarowicz

For nearly a decade, I have kept a notebook.

If I was not so poetic in my theses, I might have titled this essay On Reading the Notebooks of David Wojnarowicz. I am learning, though, to follow my poetic impulses, and to avoid didacticism. If a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose[4], then a prayer is a prayer is a prayer, or a wing is a wing is a wing. If one is able to loosen one’s didacticism, the light enters with greater ease. (I was told last night that I am too literal, that my thinking is too black and white. It was said with a smile, by the man I love. Let this be a love letter, then, to wings, to Saint David, and to the richness of flight, sky-and-land-rushing, the nuance of this shaded plane, its grey areas).

Note: silver photographic negatives, like those left by Saint David, are made of only this - grey areas. You cannot produce an analogue image without a devotion to visually expressed nuance. This gradation of silver halides, I posit, has something akin to a Godliness.

I have thought of wings, increasingly so, and have not given up the hope that I might one day grow them.

I am trying to collect these wing thoughts, to gather some meaningful poetic treatise on ascension.

Saint David on a wing, ascended and is seated at the right hand of nobody.

Saint David not buried, rather a handful of ash upon government lawns, as salt circle, as everlasting spell.

Surely the people is grass.[5]

Since I have started writing about wings, there has been a little white feather dangling from my coat sleeve. I have taken this feather as a friend and will be sad to shed it.

I have written, somewhere, of a dream I had wherein I clutched to the feathery neck of a swan, and we flew very far away.

3. Hill Rose

The boy looks up and sees a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars[6].

The better-known Saint David - Saint David of Wales (b.500, d.589) - is often associated with flight.

One day, preaching in a field in Llanddewi Brefi (surely the people is grass), the ground rose beneath him so that his voice was amplified over the valleys. As the hill rose, a white dove landed upon his shoulder, a messenger from God.

On a Sunday in January 2014 there was an incident at the Vatican wherein a trio of white doves was released into the sky, a gesture of peace. These messengers of God were promptly torn to shreds by nesting crows and seagulls. I saw the headline: Fate of White Doves Unclear After Being Released by Children Standing Alongside Pontiff.[7]

What might have happened, had the dove which lit upon the shoulder of the earlier, better-known one, been mauled by some corvid? Mightn’t the symbology of flight be somewhat dampened by this gore? There is in here somewhere the binary of ascension and descension.

Ascension - flight - is here considered possible only if unimpeded by enemy action (if we here assume the corvid to be an enemy). Our Saint David Wojnarowicz, though, ascended despite enemy action.

As salt circle.

As everlasting spell.[8]

(Fate of white doves unclear).

I wonder if that hill, that governmental lawn, rose an inch under the featherweight of his ashes.

4. Gorgeous Wings and Ill-Fated Flights

There is a 1979 live recording of Joni Mitchell singing The Last Time I Saw Richard, where, before playing her final arpeggio on the piano, she says here come my gorgeous wings now!

Before I moved to London, I thought about these words often, thought of how it might feel to fly away from home, to see the land expand and breathe, open itself on its curvature beneath:

I’ll be jovial again soon, like getting wings back. Wings of grass this time. They’ll serve their purpose, get me over there, and then I can shed them. Maybe I’ll shed them mid-flight over geometric lands, away from the thicket, ready to be catapulted to the sun.

I dream in thickets, and bramble bushes, and clearings. Safe from the angry villagers, but not without dangers. The task of untangling is thorny, fraught, but you’ve got to do it if you want your wings. Torn hem of robe. Battered foot of saint.

(2022)

Mitchell often sings of wings, of flight and its consequences, of ascension. Inside my copy of her 1971 album Blue – bought second hand – there is a folded photograph of Mitchell, in grainy black and white, wearing a feathered headdress and wings, flying through a night sky. The picture is by Norman Seeff. She looks as if soaring. I do not know how this poster got into my record sleeve, and I have never found another like it.

Mitchell mentions flight again in Amelia, on Hejira (1976).

Like Icarus ascending

On beautiful foolish arms[9]

In Amelia, Mitchell is cataloguing doomed flights. The 1937 flight of its namesake, Amelia Earhart: doomed. Icarus’ flight: famously doomed. Mitchell’s own retreat from public life: fraught, not doomed. (Hejira, an Arabic word, means, roughly, to escape hostility with your honour intact).

I have, blessedly, been rewarded thus far when choosing flight.

I like to believe that my honour, too, has remained more or less intact.

And looking down on everything

I crashed into his arms.[10]

5. Roman

How long do they live, fluttering

In and out of the shadows?[11]

At seventeen, at night, the smell of piss and bats came through my window, where outside a ruckus was afoot in the mango tree. There are many bats where I’m from. During the Summer, they screech all night, crazy off fruit juices. They are large, these bats, wingspans of a metre or more.

Around this time, I wore a t-shirt rotten with the sweat of a boy from school who I wished was a friend. I wrote in my notebook about body odour and perfume and about my friend Isabella who had recently developed an opiate addiction. I wrote of Rimbaud’s disordering of the senses. Everything that I (at this time) knew of disordered senses, I’d learnt from Isabella.

Isabella was, at this time, my confidant. Rimbaud’s sister was named Isabelle - she was his confidant. His Isabelle wore a white kerchief and worked the fields. My Isabella wrote poems about bats and wore a hospital-issue gown in the town square, laughed into the night, her pimples black on her pale face (a strange after-effect of an opiate overdose).

I copied Rimbaud’s lines into my notebook - nobody of seventeen is all that serious, not with the limes on the promenade in bloom.[12]

Saint David’s patron saint was Rimbaud.

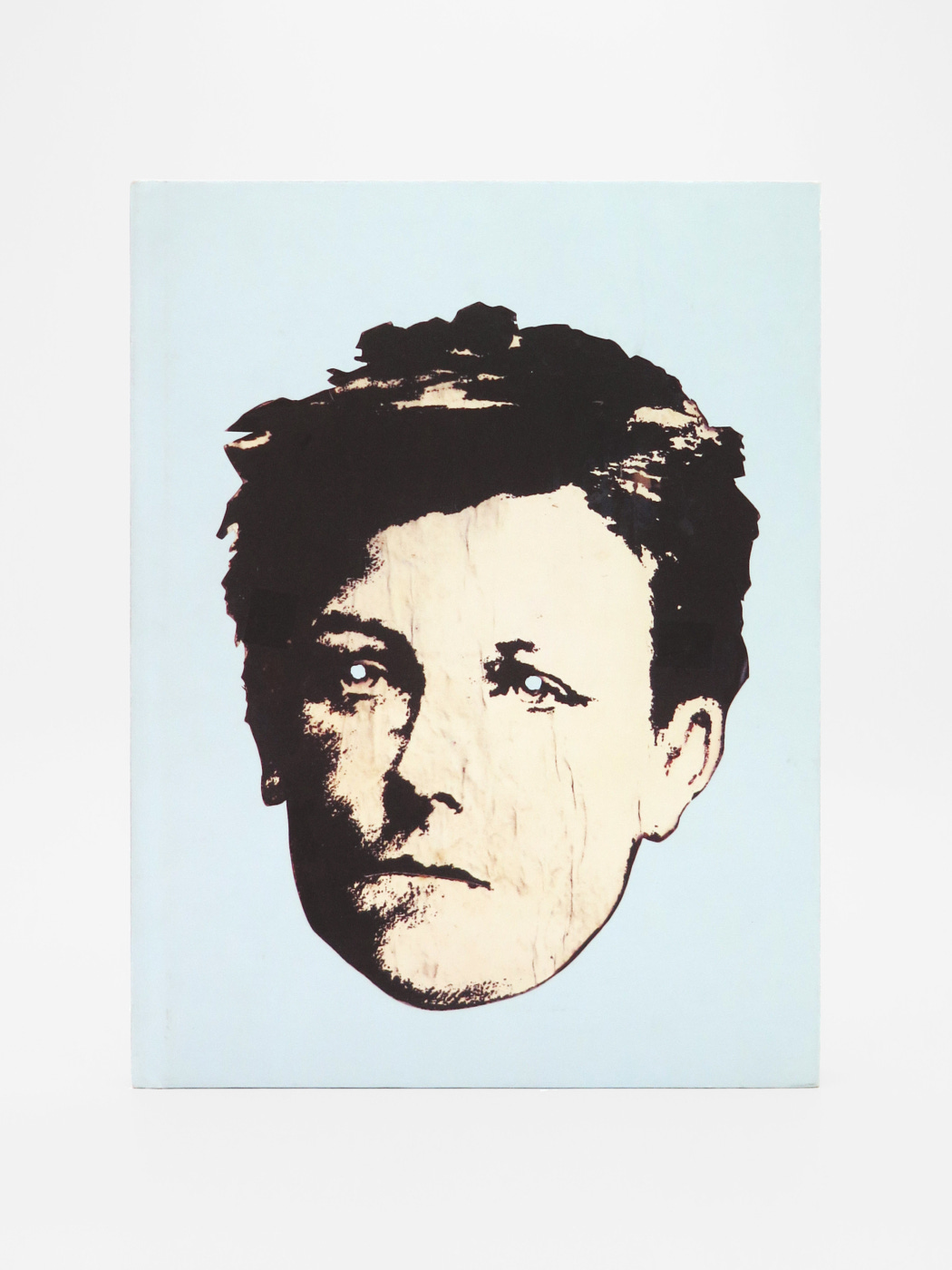

Saint David wore a xeroxed mask of Rimbaud, one of the only surviving photographs of the poet, 1871.

Wearing this mask, he staged a series of ‘self’ portraits, wherein his identity is obscured by this paper mask. Wojnarowicz’s ‘break-through’ was the 1980 publication of his Rimbaud series in the Soho Weekly News. ‘The white of the mask haunts each black and white image like a pale moon.’[13]

I had so vacant a look and so dead an expression that those who I met perhaps did not see me.[14]

Rimbaud wrote that. This vacant look is seared, in tiny dots of black ink, on the aforementioned mask, in the aforementioned photographs. A copy of a copy.

[I am] a xerox version of myself… a blank … a copy of my features.[15]

Saint David wrote that. He wrote it, in fact, in his last diary entry before his death.

If both Rimbaud and Saint David meditate on this idea of the self as a transparent composite of experiences[16], then I wonder what might be said of this essay: an annotator, revering an imitator, revering an iconoclast. I am not, I don’t think, attempting to place myself on their altar, to encroach upon their stained-glass tableaux. I am not, in any real way, claiming to have grown the wings these men have grown.

I am, though, meditating on the devotional. Saint David’s Rimbaud Series is, in effect, a rosary.

(Fluttering in and out of shadows: Rimbaud causing a scene, on the Seine, at night. Saint David on a pier, as the sun rises, stroking a stranger’s bare back. Here come my gorgeous wings!)

Like Wojnarowicz, the photocopier has always been my best friend.

There is somewhere an essay waiting to be written linking Rimbaud to the equalising format of the xeroxed zine as it was proliferated in punk and post-punk circles, but this is not that essay.

6. Ten Catalogued Flights: A Devotion

I.

In a large, labyrinthine barn near Penzance, the various detritus of my friend’s grandfather’s life rests. There are rare tractors from the thirties, piles of moth-eaten curtains, old theatre sets from pantomimes. I was most struck by a large, delicate pair of wings. Made of twisted cane and crepe paper, drained of colour, they are a faint, faded blue. The shellac crepe of them turns to dust when touched. A relic from some fair, or operetta.

In the sunny paved square outside the barn, I held the wings, their span larger than me, like an antique kite. They smelt of mice and damp. One bright morning, when this life is over.

II.

Before I boarded my first flight, I was so frightened of being separated from my Mother that I recorded a video of her reading an affirming, soothing message, to ward off homesickness. On the short flight – less than an hour – I watched this video on repeat. I did not look out the plane’s window once. When zoomed in, the digital noise of my 2007-model Panasonic camcorder made her skin look like it was made of something powdery or melting. I zoomed in until the little screen was a melted mess of pixels.

III.

I offended a swooping bird in my yard in the graveyard with the grass blades switch blades as a soft dusty angel sang.

I found this passage in an old notebook of mine: written a week after my seventeenth birthday. Remember Rimbaud’s warning, nobody of seventeen is all that serious. He wrote that when he, too, was seventeen).

IV.

Saint David, I have seen your wings on fire.

V.

There is atop my bedside table a small porcelain swan, made by a friend of mine who works in ceramics. It is small and white and somehow soft to the touch, soft as porcelain can be.

VI.

Late last night, riding bikes through Hyde Park, I said let’s stop and look at the swans! and the man I love said no, I do not like swans. The Hyde Park swans, along with the St James Park Pelicans, were what most impressed me about London when I first visited, as a boy of eighteen.

VII.

With her apron throwed over her, he mistook her for a swan,

And he shot her and killed her by the setting of the sun.[17]

VIII.

I have seen a white dove in battle with a corvid. The dove did not win.

IX.

His wings were struggling. They tore against each other on his shoulders

like the little mindless red animals they were.[18]

X.

Sorry, I thought I heard you speak. It was only your wings rustling.

7. Scruples

In closing a Catholic Rosary, one reads:

By meditating on these mysteries of the most Holy, we may imitate what they contain and obtain what they promise.

As a child I prayed each night. This habit slipped, and for a time I prayed only on Sundays. Somewhere along the way I rejected the delineation between prayer and thought, so for a while I stopped praying all together. I could not figure out how to hang-up the phone to God. (I don’t believe, now, that there is a phone to God). I would perform the sign of the cross at prayer’s-beginning, and, not remembering if I’d performed it at prayer’s-end, would find myself stuck in a compulsive pattern of performing the sign of the cross, akin to dialling-and-hanging-up a phone over and over. I was unable to find a hard reset. You might say I eventually pulled the phone’s cord from its power source.

My Mother, at age seventeen, suffered what was then, in the mid 1970s, called a nervous breakdown. (She had not read Rimbaud - nobody of seventeen is all that serious). We might now call this a mental health crisis, or a severe episode of recurrent OCD.

In the seventeenth century, these were called scruples.

As it happens, my Mother favours the archaic, and still refers to them thus.

There is, in my obsessive ritual detailed above, a faint echo of my Mother’s scruples, which were rather more severe. Think holding her breath until a Nun told her it was not a sin to breathe. Think wearing a nightgown over her boarding-school uniform in case the uniform was too revealing of the body, and therefore sinful.

(By meditating on these mysteries of the most Holy, we may imitate what they contain and obtain what they promise).

Of course, my Mother was not entirely unique in her obsession.

Saint Ignatius of Loyola (b.1491, d.1556), founder of the Jesuits, wrote “After I have trodden [upon] a cross formed by two straws, there comes to me from without a thought that I have sinned, and on the other hand it seems to me that I have not sinned… I doubt and do not doubt.” [19]

There comes to me from without. Here sin is external, something put-upon one. Purity, it follows, is internal, eternal, and innate. The white flank of a dove, unable to be bloodied.

Remember, though, that our dove did not win its battle. Fate Unclear.

Saint Ignatius, too (like our Saint David Wojnarowicz, like Saint David of Wales), is associated with wings, with flight. The Jesuits use the metaphor of roots and wings - but oh, let the wings take root and roots fly![20]

I doubt, and do not doubt.

Saint David, unlike Saint Ignatius, possessed a blessed neutrality. His education was entirely without religion - he left school at fourteen to hustle on street corners and drive in cars with married men. Unlike some of his notable contemporaries (Mapplethorpe looms large here), Saint David lacked the hang-ups and preoccupations of a lapsed, middle-class Catholicism. He was thus afforded the privilege of engaging with ascension, flight, wings, and debauchery entirely unchecked by any religious dogma.

We may imitate what they contain.

We may obtain what they promise.

8. Glory Be

At night when he is not here I place a pillow at my back it fans out from my shoulder blades like a pair of wings in half-sleep it has the gentle pressure of his embrace which warms and spirals into somewhere without space, without time.

Glory Be Saint David. If your wings of fire met mine of grass, what communion might we have, on some ramshackle roof of corrugated iron?

The rustle of grass-wing. Wings of grass, wings of wax, wings of fire.

There is a rusty grotto, somewhere, illuminated by your wings.

I have searched in many such grottoes for love, and found it not there, but in somewhere lamplit, my curtain a rag, an antler above my bed. The light shone through the smiling cheek of a man with dark curls and eyes like turtle shells.

I too have stood on a street corner, ten pounds to last me for the rest of the month, making eyes at passers-by, like you Saint David, hoping for ascension, flight.

Big white bird fly away take me now on a wing take me now big white bird fly away fly away.

March 3rd, 1989

THIS IS A SONG FOR ANGELS

THESE ARE THE HANDS

THAT ARE FILLED WITH VEINS

THESE ARE THE HANDS[21]

[1] Wojnarowicz, D. (2017). Close to the knives : a memoir of disintegration. Edinburgh: Canongate Books Ltd.

[2] Chapter 3:2. Book of Exodus.

[3] Wojnarowicz, D. (2017)

[4] Stein, G. (1922). Sacred Emily. In: Geography and Plays. Boston: Four Seas Company.

[5] Chapter 40:6-8. Book of Isaiah.

[6] Gilchrist, A. (1863). The Life of William Blake.

[7] Associated Press in Vatican City (2014). Pope’s peace doves attacked by crow and seagull. [Online] the Guardian.

[8] Note: David Wojnarowicz’s ashes were scattered on the White House lawn, after his AIDS-related death. He is perhaps best known for the print on the back of his jacket, as seen at a rally in the late 1980s: If I die of AIDS - forget burial - just drop my body on the steps of the FDA.

[9]Mitchell, J. (1976). Amelia. Asylum Records.

[10] Mitchell, J. (1976).

[11] Oliver, M. (2007). Messenger. In: Thirst. Bloodaxe.

[12] Rimbaud, A. (2004). Roman. In: Collected Poems and Letters. Penguin UK.

[13] Wood, C. (2006). David Wojnarowicz: Cabinet / Between Bridges, London, UK. Frieze, (100).

[14] Rimbaud, A. (2004). Selected Poems and Letters. Penguin UK.

[15] Wojnarowicz, D. (2000). In the Shadow of the American Dream. Grove Press.

[16] Wood, C. (2006)

[17] Polly Vaughan (Ballad 166). In: Roud Folk Song Index.

[18] Carson, A. 1998. Autobiography of Red. Cape Poetry.

[19] Meissner, W. (1992). Ignatius of Loyola: The Psychology of a Saint. Yale University Press.

[20] Jimenez, J.R. Quoted by Hirsch, E. (1999) In How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry. Harcourt Brace and Company.

[21] Wojnarowicz, D. (2000).